17th and 18th-century Southeast Asia was a region of ‘Multiple Centres of Diplomacy’. Of all the thousands of diplomatic manuscripts (Malay: “Surat Emas”) with their own original seals exchanged between the various rulers, kings and sultans in the region, hardly any originals survive. Some original manuscripts still extant in scattered libraries around the world represent a high cultural value in terms of language and writing traditions, as well as material value. During the VOC period from the foundation of Jakarta (1619-1799), Batavia Castle was an active diplomatic centre in the Southeast Asian region and beyond. Thousands of incoming and outgoing letters from and to Asian rulers and dignitaries testify to the sheer volume of these exchanges of letters and gifts were, and how Europeans adapted themselves to Asian diplomatic customs and the system of gift exchanges.

The VOC Supreme Government in Batavia Castle received letters from Asian rulers on a weekly basis. Its Translation Department was busy making translations from letters in Javanese, Malay, Bugis, Chinese and Arab. Most of the letters were from Indonesian rulers. Diplomatic delegations from Banten or Ternate, or Siam or Tonkin were all received with the appropriate honour, protocol and ceremony. Diplomats were welcomed by high VOC officials on the quay of Sunda Kelapa harbour. The official welcomes over they were taken for a sightseeing trip through Batavia in horse-drawn carriages, passing along the most impressive streets and canals, and seeing the Town Hall (Stadhuis) and the imposing entrance gate of the Batavia Castle. Once received with the appropriate military salutes in Batavia Castle, the diplomats offered their monarch’s beautifully decorated, “Surat Emas” or “Golden Letter”. According to Asian diplomatic custom, the letters were offered to the Governor-General in a yellow-silk envelope on a silver plate. All “Surat Emas” were read aloud in the audience room in the original Asian languages used in their original composition be it Malay, Javanese, Buginese or Chinese.

After the formal ceremony of the public reading, the diplomatic letters were immediately sent to the Castle’s Translation Department to be rendered into Dutch, the resulting translations then being inserted in the Daily Journals. This is how the content of the individual letters has survived for posterity. Subsequently, the Dutch texts of the formal responses by the Supreme Government to the respective Asian rulers were also inserted in the Daily Journals.

Unfortunately, the originals of the beautifully decorated “Surat Emas” and other letters, were not preserved at Batavia Castle during the 17th and 18th centuries. The reason for this is unclear: the originals may have lost their value once they were translated t or they may simply have been discarded or were given as a perk to interested individuals who profited from their gold leaf and other rich decorations. Exactly the same situation is found in the English East India Company archives now kept in the India Office Records of the British Library, where there are almost no original Malay or other foreign original royal letters. Even in the various collections of “Raffles letters” there are hardly any originals . The small collections of original letters sent to the VOC or EIC, which have survived, are found in individual collections rather than institutional ones.

There are two major exceptions:

- Almost all the diplomatic correspondence in Malay – about 500 letters in all - which came to Batavia Castle during the 1790-1820 period, the era of transition from the VOC to the post-January 1818 Netherlands Indies state, is now kept in Leiden University Library and have been described in E.P. Wieringa (ed.), Catalogue of Malay and Minangkabau Manuscripts in the Library of Leiden University [...], Leiden University, 1998).

- In 1743-1744, Governor-General G.W. van Imhoff’s (in office, 1743-50) administrative reforms meant that diplomatic letters were no longer included in the Daily Journals of Batavia Castle. From 1750 onward they were archived seperately in the series of Incoming and Outgoing Missives from Indigenous (Asian) rulers. These letters are all translated in Dutch at that time. Only about one hundred original letters and their translations survive in ANRI from the late eighteenth century.

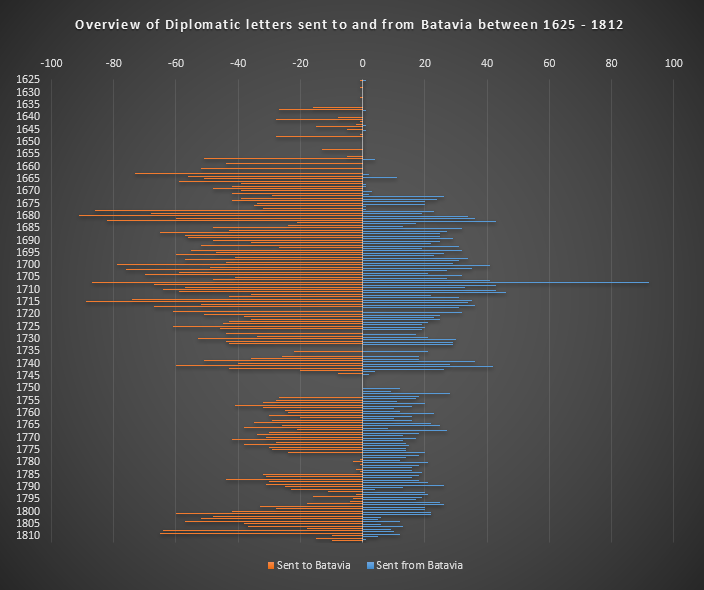

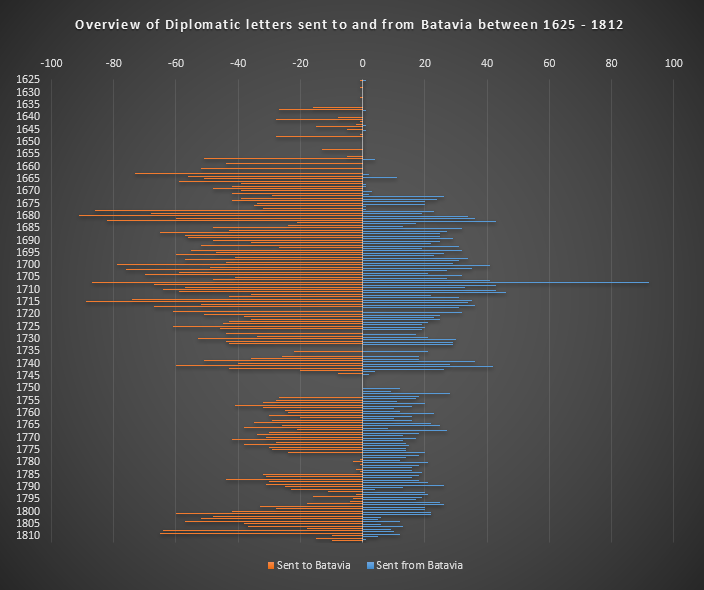

This website offers a complete entry to all translated incoming and outgoing diplomatic letters included in the Daily Journals of Batavia Castle and the series of Incoming and Outgoing Missives. The graphic overview shows that the amount of incoming letters was always larger than the amount of outgoing letters.

The VOC archives in the National Archives or Nationaal Archief in The Hague contain many copies of the incoming letters of Asian rulers. These letters are catalogued in the VOC databases of TANAP. Every one of the catalogued archives of the thirty-five former VOC establishments in Asia has a section called “correspondentie met inheemsen”, meaning correspondence with regional or local rulers and kings. Many letters found in the Daily Journals, can be found here as well. But the TANAP database offers more, namely a listing of the literally thousands of incoming and outgoing letters generated at the regional level, see http://databases.tanap.net/vocrecords/

The database of diplomatic letters provides both the rulers’ names and the geographical locations of both the senders and receivers.

The rulers are mentioned by the names and spelling given in the archives as well as by their currently accepted orthographs. It was often difficult to trace and verify all of them and many names are still in need of further research. Many of these rulers were known by names that included the titles and royal styles of their ancestors while they also kept using birth names or other names for different occasions, including the signing of letters. Many times these rulers were only known by their royal titles, while their birth names remain obscure or rarely used.

The rulers are mentioned by the names and spelling given in the archives as well as by their currently accepted orthographs. It was often difficult to trace and verify all of them and many names are still in need of further research. Many of these rulers were known by names that included the titles and royal styles of their ancestors while they also kept using birth names or other names for different occasions, including the signing of letters. Many times these rulers were only known by their royal titles, while their birth names remain obscure or rarely used.

VOC clerks were often inconsistent or careless in the use of names and formal titles of the rulers, princes and other dignitaries to whom letters were addressed; or they used names which are today either untraceable in the archives or simply incorrect. Therefore, it may be very confusing to keep track of who is who. To improve the traceability of the rulers cited in these letters, most of the royal names and titles from the Daily Journals are given in modern spelling in the letter database. It is advisable to search in both the ruler names as well as the geographical locations to cover all relevant sources. Correspondents who changed their titles, and might thus have double entries, can still be traced geographically.

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar