Introduced Jeyamalar Kathirithamby-Wells

Jeyamalar Kathirithamby-Wells, “Report from the Minister of Banten Tsiely Godong and former translator of the English Harkis Baly concerning the English presence in Silebar and Bengkulu, West-Sumatra, 1696”. In: Harta Karun. Hidden Treasures on Indonesian and Asian-European History from the VOC Archives in Jakarta, document 12. Jakarta: Arsip Nasional Republik Indonesia, 2013.

By Jeyamalar Kathirithamby-Welss

By the mid-sixteenth century, Bengkulu joined the rest of the west coast of Sumatra as a major exporter of pepper attracting the ambitions of the neighbouring state of Banten across the Sunda Straits. With the aim of augmenting its own pepper supplies, historians presume that Banten gained access to Sumatran pepper when Sultan Hasanuddin (r. 1552-70) married the daughter of the ruler of Inderapura, receiving as dowry all the coastal areas to the south. Subsequently, Tuan Pati Bangun Negara and Bangsa Radin, chiefs respectively of the Redjang-Lebong and Lemba of Sungai Lemau and Silebar, received the title of pangeran(prince, governor) from the Sultan of Banten. This is recorded by some copper plates dating back from 1668 (A.H. 1079).[1] Their empowerment was aimed, evidently, at securing their cooperation to boost Banten’s pepper supplies.

Years of Anglo-Dutch rivalry in Banten over the pepper deals with the local rulers culminated during an internal Bantenese power struggle in 1682. The outcome led to the withdrawal of the English East India Company from its factory there. Consequentely, the British had to search for an alternative access to the pepper market in Sumatra. Pre-empted by the VOC in Pariaman (north of Padang), the English East India Company turned to Bengkulu. Here, in July 1685, the Company signed a treaty with the pangeran of Sungai Lemau and Sungai Itam, gaining exclusive delivery of pepper at a fixed price of 12 dollars per bahar (fixed, later, at 560 pounds) and land for a settlement, upon which they raised the robust Fort Marlborough, which survives to this day.[2]

Though the Dutch in Banten – no less than the British in Bengkulu – were keen on avoiding hostilities, they had much to profit from a successful Bantenese challenge to British access to the pepper fields of west Sumatra. Thus, in December of 1685, prompted by the VOC to dislodge the British, Sultan Abu Nasr Abdul Kahar (r. 1682-7) sent to Silebar a 2-300 strong force conveyed by a Dutch fleet under the command of a jenang(representative/ambassador), Karia Sutra Gistra. The British position was saved by a combination of factors, principally, the pangerans’ flight to the hinterland; the outbreak of disease among the invading forces; and the lack of Dutch reinforcements which compelled the Bantenese withdrawal.[3] This left the British free to conclude a treaty with another local ruler, the pangeran of Silebar, who controlled the only safe anchorage for ships visiting the West Sumatran coast, at Pulau Bay.

Though in 1688 the British successfully expelled the Bantenese from collecting pepper at Silebar, Banten did not relinquish hopes of pressing its claim over the area. Hence, menteri Tsiliey Godong was commissioned in 1696 by Pangeran Kesatrian to investigate the state of affairs in Bengkulu. The report he wrote on returning to Banten was in cooperation with Harkis Baly, a resident of Bengkulu and former interpreter for the British who was in Banten on a private visit. The historical validity of the report, favourable to advancing Banten’s claim, may be evaluated with the benefit of local British reports.

The price paid for pepper by the British was indeed 12 Spanish dollars per bahar as Tsiliey Godong reported; but the ‘toll’ referred to was the commission of 1 dollar per bahar payable to the pangeran on pepper delivered by areas under their respective jurisdiction. It was in lieu of their now-relinquished right to impose hasil (export duty), a distinct feature of their customary authority, exercised for preferential or monopoly control over trade. The pangeran of Selibar was understandably reluctant to renounce a lucrative source of income derived from Silebar’s pre-eminence as the main centre for the export of southwest Sumatran pepper. The East India Company granted in a written settlement to him a compensatory annuity of only 400 Spanish dollars.[4] In addition to hereby securing transfer of the pangeran’s control over the pepper trade, the Company proceeded to impose port duties allowing him no share in the revenue.

The trade arrangements between the East India Company and Sumatran leaders appear to have weighed heavily in favour of the British, leaving shortfalls in local expectations, which the report represented as a loophole Banten might well exploit to assert its influence. The fact remained, however, that the British contracted a higher price in Spanish dollars for pepper,[5] compared to payments offered, often in rice and provisions by Chinese, Javanese and other traders, including those licensed by the ruler of Banten. Additionally, British presence promised security and stability, not guaranteed by the customary visit of Banten’s jenang(representative) every 2-3 years, essentially to make new appointments and claim taxes and tribute.[6]

The perceived injustices of the British in their dealings with the pangeran, portrayed in Tsiely Godong’sreport, supported Banten’s bid to expel the British, if necessary by force. Hence, close and accurate information on the layout of the British defences, including details of the fortification, were crucial and who better to provide such intelligence than Harkis Baly. However, it would appear that Dutch reluctance to offer military aid for fear of umbrage with the British ruled out renewed aggression. Instead, in response to the subsequent contracts the British made with Manna and Krue – areas to the south of Bengkulu – Sultan Mahassin Zainal Abidin (r. 1690-1733) tried a strategy of negotiation for asserting his claims. On the basis of intelligence brought to Banten by two Sumatrans, ‘Raja Tonkas and Malla’, a jenang was dispatched in 1729 to return the men and install them as local heads. On the same occasion, the jenang conveyed a letter from the Sultan offering the British the coast from Manna to Nassal (north of Krue), with full powers to administer the region, upon payment of 10,000 Spanish dollars. In response, the British returned the ambassador with a promise to refer the matter to the Directors and let the matter rest.[7]

Caution over extending British influence further south towards Krue soon changed given the repeated invitations for trade and settlement received from local chiefs, Banten’s weak control in the region and the absence of any Dutch claims in the area. But, above all, it was feared that British inaction would merely encourage Banten’s claims to the entire coast up to the borders of Inderapura. In 1742 the British occupied Pulau Pisang, an important southern point for pepper collection, but only some four year later did Banten stage a protest. The rumoured attack by the Bantenese Radin was followed by a letter from Sultan Arifin (r. 1733-48) threatening to appeal to the Dutch should the British fail to withdraw immediately. Returning the stock ‘civil answer’ that the matter would be referred to Europe,[8] the British successfully bought time which, in the event, saw the eruption of trouble in Banten, fanned by the political intrigues of the ruler’s wife, Ratu Sharifa Fatima, which culminated in the Banten Rebellion of 1751-52. [9]

By the time Banten entered Dutch vassalage in 1752, the proliferation of private trade involving Malay, Chinese, Buginese and European participation undermined the VOC’s claims over Banten’s major source of pepper from Lampung. Much of it entered British hands removing the need for further British expansion. By 1763, a stone planted by the VOC at Flat Point (Vlakke Hoek) in Semanka Bay firmed up the boundary between the two rival European powers, fulfilling their mutual desire to avoid conflict.[10] Semangka, which entered British hands during the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War (1780-84), was duly reoccupied in 1785. The exchange of the British Sumatran territories for Melaka, under the Anglo-Dutch treaty of 1824, finally settled contending claims over Bengkulu paving the way for its ultimate integration into modern Indonesia.

[1] J. Kathirithamby-Wells, The British West Sumatran Presidency (1760-85), Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press, 1977, 21. For the respective interests of Banten, the British and the Dutch in Bengkulu see P. Wink, ‘Eenige Archief stukken betreffende de vestiging van de Engelsche factorij te Benkoelen in 1685’, TBG, 64 (1924): 461-3.

[2] Ibid., pp. 5-6; John Bastin, The British in West Sumatra (1685-1825), Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press, 1965, xii-xvi, 1-12; British Library, India Office Records: East India Company Factory Records, Sumatra Factory Records, Vol. 2 (1685-1692), 6 Nov. 1686. For the text of the treaty, see H. Dodwell, Records of Fort St. George. Letters from Fort St. George for 1688, Madras: Government Press, 1919, vol. 3, 3 July 1685, 205-7.

[3] Bastin, The British in West Sumatra, 17, 20-6; Sumatran Factory Records, vol. 2, Benjamin Bloom to Karia Sutra Gistra, ? Jan. 1985.

[4] Bastin, The British in West Sumatra, 4, 37-8; Kathirithamby-Wells, The West Sumatran Presidency, 32.

[5] During the early years, when payment for pepper was offered in cloth and copper coins to meet the shortage in Spanish dollars, the Sumatrans showed their discontent by smuggling produce to other buyers, compelling the Bengkulu administration to establish silver as the linchpin of its monopoly.

[6] For Banten’s commercial relations with Silebar in the pre-British period see See J. Kathirithamby-Wells, ‘Banten: A West Indonesian Port and Polity’, in J. Kathirithamby-Wells and John Villiers, The Southeast Asian Port and Polity: Rise and Demise, Singapore: Singapore University Press, 1990, 116-17.

[7] Sumatra Factory Records, Vol. 8, 30 Oct. 1729.

[8] Sumatra Factory Records, Vol. 9, 28 July 1742.

[9] For an account of these events see Ota Atsushi, Changes of Regime and Social Dynamics in West Java: Society, State and the Outer World of Banten, 1750-1830, Leiden: Brill, 2006, 59-74.

[10] Kathirithamby-Wells, The West Sumatran Presidency, 139-40.

Jeyamalar Kathirithamby-Wells, “Report from the Minister of Banten Tsiely Godong and former translator of the English Harkis Baly concerning the English presence in Silebar and Bengkulu, West-Sumatra, 1696”. In: Harta Karun. Hidden Treasures on Indonesian and Asian-European History from the VOC Archives in Jakarta, document 12. Jakarta: Arsip Nasional Republik Indonesia, 2013.

Sourse: https://sejarah-nusantara.anri.go.id/hartakarun/item/12/

OLD DUTCH TEXT

OLD DUTCH TEXT

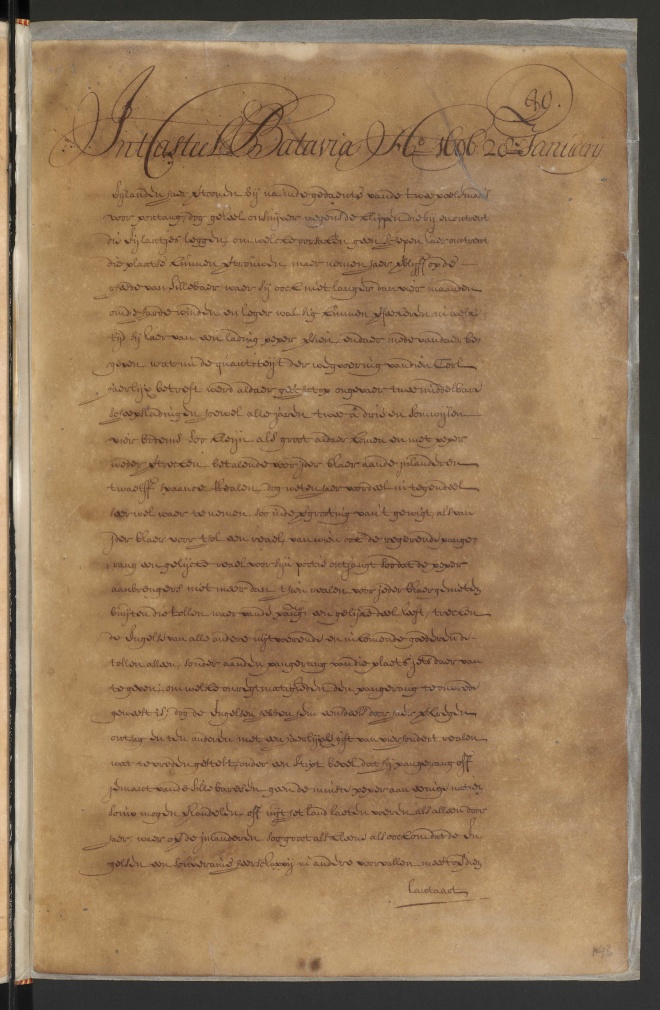

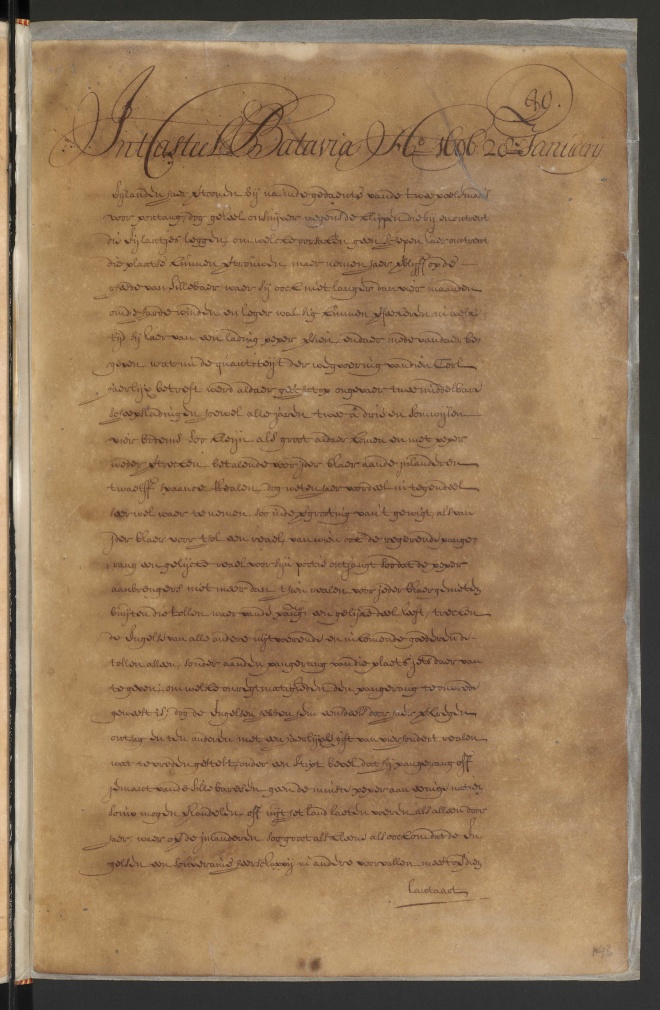

Relaas over Silebar en Benkulen en de activiteiten van de Engelsen aldaar, 28 januari 1696.

[48]

Relaas gedaen door den mantry des Sultans van Bantam genaamt ’t Siliely Godong en Harkis Baly, gewesen tolck der Engelsen op Bankahoelo en tot nog een inwoonder aldaer, wegens de constitutie van Sillebaer etc., sijnde de eerstgenoemde naer verrigting sijner meesters beveelen den Pangerang Cassatrian op den 17e january anno 1696 van daar geretourneert ende de andere om sijn eigen affaires hier gekomen, dog ieder in ’t bijsonder ondervraegt en sodanig gelijck volgt verhaalt.

Dat Sillebaer en Bankahoelo in gelijke forma leggen als Bantam en Pontang, excepta dat voor de bay van Sillebaer geen eylanden sijn, maar wel voor Bankahoelo alwaer twee [49] eylanden haer vertoonen, bijna in de gedaente van de twee poele madis voor Pontang, dog geheel onsuyver wegens de klippen die bij en omtrent die eylantjes leggen, om welcke oorsaken geen schepen haer omtrent die plaatse kunnen vertrouwen, maer nemen haar verblijff op de rheede van Sillebaer waer sij oock niet langer dan vier maanden om de harde winden en leger wal sig kunnen verseekeren, in welke tijd sij haer van een lading peper versien, en daer mede van daer begeven.

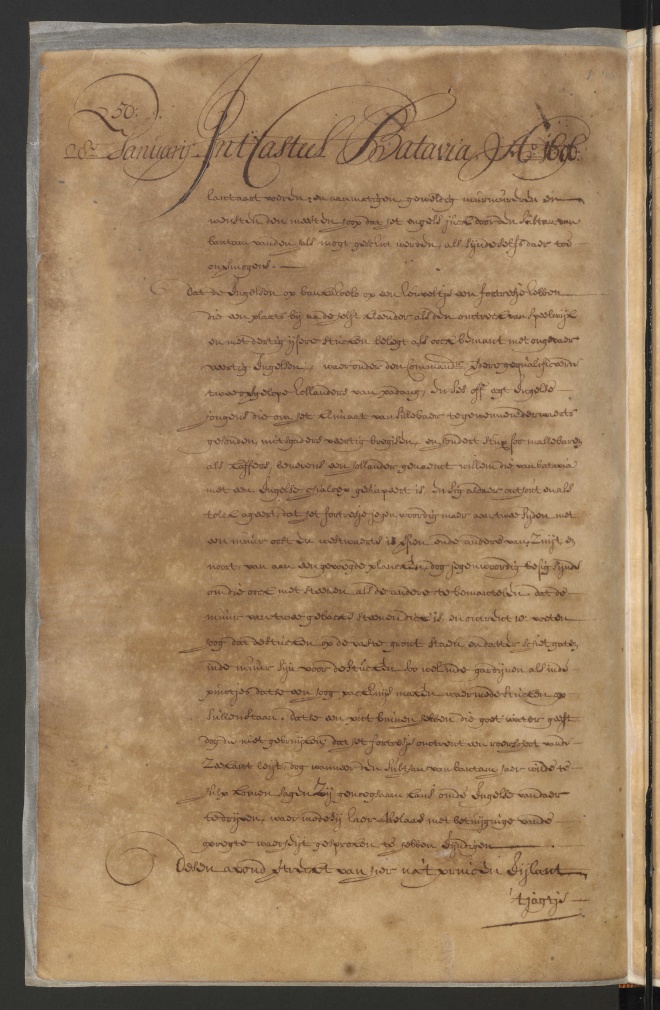

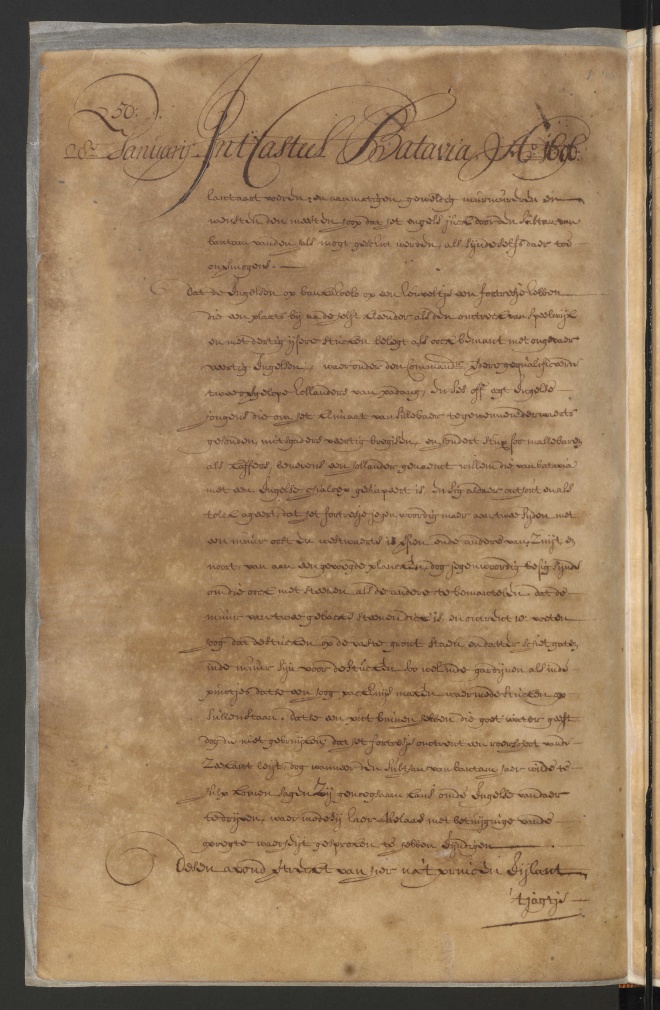

Wat nu de quantiteyt der wegvoering van dien corl jaerlijx betreft, werd aldaer geschat op ongevaer twee middelbare scheepsladingen, hoewel alle jaren twee â drie en somwijlen vier bodems, soo kleyn als groot, aldaer komen en met peper weder vertrecken, betalenden voor ider bhaer aan de inlanderen twaelf Spaance realen, dog weten haer voordeel integendeel seer wel waer te nemen, soo in de vergrooting van ’t gewigt, als van ieder bhaer voor thol een reael, van wien ook de regerende Pangerang een gelijcke reael voor sijn portie ontfangt, soodat de peperaanbrengers niet meer dan thien realen voor ieder bhaer genieten buyten die tollen waervan de Pangerang een gelijke deel heeft, trecken de Engelse van alle andere uytvoerende en inkomende goederen de tollen alleen, sonder aan den Pangerang van die plaats iets daarvan te geven, om welke onregtmatigheden den Pangerang te onvrede geweest is, dog de Engelsen hebben hem eensdeels door haer verkregen ontsag, en ten anderen met een jaerlijxse gift van vierhondert reaelen wat tevreden gestelt, onder een stipt bevel dat sij Pangerang off iemant van de Sillebaresen geen de minste peper aan eenige natiën souw mogen verhandelen, off uyt het land laeten voeren als alleen door haer, waerover de inlanderen soo groot als kleene, alsoock omdat de Engelsen een souveraine heerschappij in andere voorvallen meest over dien [50] lantaart voeren, en aanmatigen, geweldig murmureren en wensten den meesten hoop dat het Engels juck door den Sultan van Bantam van den hals mogt geschut werden, als sijnde selfs daertoe onvermogens.

Dat de Engelsen op Bankahoelo op een heuveltje een fortresje hebben die een plaats bijna de helft kleender als den omtreck van Speelwijk, en met dertig ijsere stucken belegt, alsoock bemant met ongeveer veertig Engelsen, waeronder de commandeur, verdere gequalificeerde, twee overgelope Hollanders van Padang, en ses off agt Engelse jongens die om het klimaat van Sillebaer te gewennen derwaerts gesonden, mitsgaders veertig Boegisen, en hondert stux soo Mallebaren als kaffers, benevens een Hollander genaemt Willem die van Batavia met een Engelse chialoep gesiapeert is, en sig aldaer onthout en als tolck ageert, dat het fortresje jegenwoordig maer aan twee sijden met een muur oost en westwaerts is versien, en de andere van zuyt en noort, van aaneengevoegde plancken, dog jegenwoordig besig sijnde om die oock met steenen als de andere te bemantelen; dat de muur van twee gebacke steenen dick is, en omtrent 10 voeten hoog; dat de stucken op de vaste gront staen, en datter schietgaten in de muur sijn voor de stucken, soowel in de gordijnen als in de puntjes; dat se een hoog packhuys maken waer mede stucken op sullen staan; dat se een put binnen hebben die goet water geeft dog die niet gebruyken; dat het fortresje omtrent een roerschoot van de zeekant leyt, dog wanneer den Sultan van Bantam haer wilde te hulp komen, sagen zij genoegsaam kans om de Engelse van daer te drijven, waermede sij haer relaas met betuyginge van de opregte waerheyt gesproken te hebben, eyndigen.

Artinya:

Laporan tentang Silebar dan Bengkulu serta kegiatan orang-orang Inggris di tempat-tempat tersebut, 28 Januari 1696.

[48]

Laporan yang dibuat oleh mantri Sultan Banten bernama Siliely Godong dan Harkis Baly, mantan penerjemah untuk orang-orang Inggris di Bankakoelo dan sekarang masih tinggal di tempat itu sebagai seorang penduduk biasa berdasarkian undang-undang Silebar dsb, dan yang tersebut pertam, sesudah melaksanakan perintah majikannya Pangeran Cassatrian, pada tanggal 17 Januari 1696 telah kembali ke tempat itu, dan yang seoorang lagi sudah tiba di sini untuk urusannya sendiri, namun masing-masing telah ditanyai dan memberikan serta menyampaikan hal-hal seperti berikut ini.

Bahwa letak Sillebaer dan Bankahoelo sama seperti letak Banten dan Pontang, kecuali bahwa di depan teluk Sillebaer tidak terdapat pulau-pulau, tetapi di depan Bankahoelo nampak ada dua [49] pulau, yang bentuknya mirip dengan dua pulau madis yang ada di depan Pontang, namun tidak sama benar karena terdapat batu-batu karang di sekitar pulau-pulau tersebut, yang menyebabkan tidak ada kapal yang bersedia berlayar di sekitarnya tetapi memilih untuk membuang sauh di dermaga Sillebaer dan di tempat itu pun mereka tidak dapat tinggal lebih dari empat bulan untuk menghindari tiupan angin yang kencang dan tepi daratan yang rendah, dan selama waktu itulah mereka harus melakukan bongkar-muat lada lalu pergi dari tempat itu.

Mengenai besaran biji-biji lada yang diangkut setiap tahunnya, diperkirakan berjumlah sekitar dua muatan kapal berukuran sedang, kendati selama bertahun-tahun ada dua hingga tiga, dan terkadang empat kapal, baik kecil ataupun besar, yang singgah di sana dan kemudian berlayar pergi dengan mengangkut muatan lada, dan membayar dua belas real Spanyol untuk setiap muatan kepada penduduk pribumi, akan tetapi mereka masih mampu mengambil keuntungan yang memadai dengan memperberat timbangan muatan dan juga dengan memungut pajak satu real untuk setiap bahara (bhaer), dan Pangeran yang memerintah juga memperoleh bagiannya, sehingga mereka yang memasok lada menerima tidak lebih dari sepuluh real untuk setiap bahara. Di atas semua pajak yang Pangeran juga menerima bagiannya itu, orang-orang Inggri masih jugas memungut pajak atas semua barang yang keluar dan masuk, tanpa memberi apa-apa kepada Pangeran setempat, sehingga menyebabkan Pangeran tidak puas dengan penyimpangan tersebut, akan tetapi orang-orang Inggris telah dapat mengambil hati Pangeran dengan kewibawaan mereka dan dengan memberikan hadiah tahunan bernilai empat ratus real, disertai perintah ketat kepada Pangeran atau orang-orang Sillebar bahwa mereka tidak diperbolehkan memperdagangkan atau pun mengangkut keluar lada sedikit pun, kcuali kepada orang-orang Inggris dan orang-orang Inggris itu juga memiliki kekuasaan dalam hal-hal lain terhadap suku-suku [50] tersebut, dan mereka mengaku-ngaku berkuasa sehingga penduduk pribumi, yang berkedudukan tinggi maupun rendah, merasa sangat tidak puas dan sebagian besar dari mereka berharap agar penindasan oleh Inggris itu dapat dienyahkan oleh Sultan Banten, karena mereka sendiri tidak mampu berbuat demikian.

Bahwa orang-orang Inggris mendirikan sebuah benteng kecil atau kubu di atas bukit yang luas lapangan di dalamnya hampir separuh dari luas lapangan demikian di benteng Speelwijk. Benteng kecil itu dilengkapi dengan tiga puluh meriam besi dan dijaga oleh sekitar empat puluh serdadu Inggris, di antaranya seorang komandan, dan selanjutnya dua orang Belanda yang telah membelot dari Padang, lalu ada enam atau delapan laki-laki remaja Inggris yang dikirim ke tempat itu untuk menyesuaikan diri mereka dengan iklim di Sillebaer, dan empat puluh orang Bugis dan sekitar seratus orang Mallabar dan budak termasuk seorang Belanda bernama Willem yang telah memiliki surat izin, dan tiba di sana dengan menggunakan sebuah perahu jenis sialup Inggris dan tinggal di sana serta bertindak sebagai penerjemah; bahwa dewasa ini kubu tersebut hanya memiliki tembok di dua sisinya sebelah timur dan barat, dan sisi-sisi selatan dan utara hanya diberi papan-papan, tetapi sekarang ini di sekeliling kedua sisi tersebut juga sedang dibangun tembok batu seperti sisi-sisi lainnya; bahwa tebal tembok kubu dua batu bata dan tingginya sekitar 10 kaki; bahwa meriam-meriam diletakkan secara permanen di atas lantai dan bahwa terdapat lubang-lubang tembak di tembok di depan meriam-meriam itu dan juga di tembok tirai kubu serta di sudut-sudut bastion; bahwa mereka membangun sebuah gudang yang tinggi yang di atasnya akan diletakkan meriam-meriam; bahwa di dalam kubu terdapat sebuah sumur yang berisi air yang baik tetapi mereka tidak memanfaatkannya; bahwa kubu itu terletak sekitar satu tembakan meriam dari sisi laut, namun apabila Sultan Banten bersedia memberi bantuan kepada mereka, maka mereka akan dapat menghalau orang-orang Inggris dari tempat itu, dan dengan itu mereka mengakhiri laporannnya dengan menyatakan bahwa telah mengatakan yang sebenarnya.

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar